|

The western has always enjoyed enormous and enduring popularity, and it's not difficult to see why. It's a perfect vehicle for escapism. It gives us action, adventure, mystery and romance set against a backdrop of some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. At its best, however, the western is also a morality play. It carries a message of hope (that we can survive and make good in the great, untamed wilderness) and a reaffirmation of justice (that good really does triumph in the end), and as such, it is very hard to beat.

In The Pulp Western (Borgo Press, 1983), John A Dinan states that "the cowboy of fiction survives because of the genius of first-rate authors like James Fenimore Cooper and such modern masters of the art as Fred Glidden (Luke Short) and Ernest Haycox."

He may well be correct in this assertion, but I have always felt that our love of the American West is far more likely to have been nurtured by the lesser works of the so-called "hack" writers.

|

|

|

|

The earliest westerns, of course, were the dime novels, a genre which began with Seth Jones, or The Captives of the Frontier (Beadle & Adams, 1860), by school teacher Edward Sylvester Ellis. When this cheap little paperback went on to sell a staggering 500,000 copies, the dime novel was born.

The best-known, and certainly most successful, of all the dime novelists was Ned Buntline. Born Edward Zane Carroll Judson in 1823, Buntline ran away from home when he was just ten years old, and went to sea as a cabin boy. Returning home several years later, he tried his hand at writing and quickly became one of the most successful writers of his day. His personal life was far more interesting -- and adventurous -- than that of any of his heroes, however. Married at least eight times, he also found the energy to conduct a positive string of affairs. At his height, his writings also earned him more than $20,000 a year -- a phenomenal sum at the time.

Buntline and his fellow scribes had one thing in common, however -- a spectacular ignorance of the west. It was painfully obvious from their purple prose and meandering, wildly implausible plots, that the dime novelists neither knew nor researched their subject. Indeed, one particular pulpster called himself "Wyoming Bill" for no other reason than that he had once been through Wyoming on a train! Still, there can be no denying that the dime novelists gave their readers exactly what they wanted -- thrills and spills a-plenty.

|

|

|

|

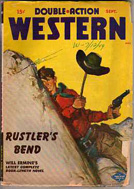

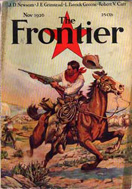

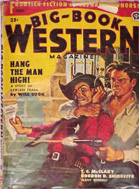

The age of romantic innocence which so characterized the dime novels ended in the 1930s, by which time more than 4000 yarns of variable quality had been published to satisfy a thrill-hungry public. Now the dime novel was replaced by the western pulp, and the next thirty years saw the creation -- and cancellation -- of more than two hundred western pulp magazines, the most famous of which was probably Western Story Magazine.

|

|

|

Max Brand was undoubtedly the biggest name to come out of the pulps. Born Frederick Schiller Faust in Seattle, Washington, on 29th May 1892, he later traveled the world as a drifter and soldier before becoming a writer. A prolific wordsmith, Faust's work eventually appeared under eighteen different pseudonyms, the most famous of which was Max Brand. Although he died in 1944, whilst serving as a war correspondent in Italy, it is a mark of his popularity that his books still sell more than one million copies every year.

The western might have undergone a subtle change, but the basic themes, characters and resolutions remained the same. Action was everything, and anything that got in the way of the action was, well, lower'n a snake's belly in a wagon-rut. Bill Burchardt, one of the top pulp western writers of his day, always tried to create yarns out of "basically real situations, but making everything larger than life and strictly entertainment-orientated". Another western giant, Frank Gruber, went one step further and broke the western down into seven distinct categories:

The Union Pacific Story

The Ranch Story

The Empire Story

The Revenge Story

Custer's Last Stand

The Outlaw's Story

The Marshal's Story

I wonder why he never thought to add "The Woman's Story", or "The Indian's

Story"?

As you might imagine, writing for the pulps was a tough and demanding school where only the fittest survived. "I learned more about writing for the pulps than any other publication,"

Louis L'Amour later declared. "Their demand was for a no-nonsense type of writing, and if one made a living at it, there was no time for sitting about twiddling the thumbs."

The western pulps never really considered characterization especially

important. Indeed, the only three stories Max Brand ever had rejected were the ones in which he tried to develop his protagonists. But not all the stories of the period were without such depth, and this is a good place to pause a moment and take a closer look at three of the more influential western writers of the time.

Zane Grey began a life-long love affair with the great outdoors

at a very early age, and unlike the dime novelists of his youth, he actually researched his stories thoroughly. Unencumbered by strict deadlines, he was able to spend upwards of three months on every book he wrote -- hence his greater emphasis on character and character development. Although

he is considered somewhat dated today, I would still recommend 30,000

on the Hoof, an epic yarn which cannot fail to sweep the reader along.

Ernest Haycox grew up in the logging camps of Portland, Oregon, served with the National Guard on the Mexican border and later fought in France during World War I. He started writing whilst still at college and sold his first short story in 1921. Haycox developed quickly as a western writer, and his novels are remarkable primarily for their meticulous attention to plot and historical authenticity. Anyone who reads Man in the Saddle, Rim of the Desert, The Border Trumpet or Bugles in the Afternoon will quickly discover this author's obvious strengths for themselves.

In a career that spanned four decades, Illinois-born Luke Short

(real name Frederick Dilley Glidden) penned fifty top-notch westerns. A failed journalist, Short worked as a logger and archaeologist's assistant before turning his attention to western fiction. Good pacing, credible plots and original, believable characters distinguish his work, and among the best of it you will find such classics as Sunset Graze, Bold Rider and Ambush.

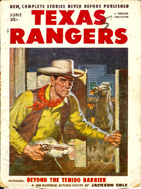

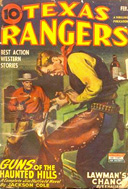

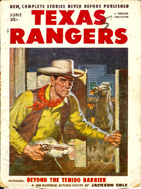

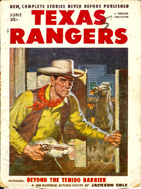

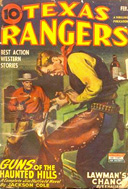

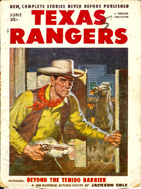

The western pulps also pioneered the continuing (or series) character, and nowhere was this more apparent than in Texas Rangers, every issue of which chronicled the adventures of Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield.

Hatfield's gun-swift escapades were penned by Jackson Cole,

which was actually a house-name behind which labored a whole team of writers. Alexander Leslie Scott is the writer most associated with the pseudonym. He started writing westerns whilst still in his early twenties, and tried whenever possible to base his plots upon his own first-hand experiences. A prolific penman, he also went on to compose about 125 stories in the Walt Slade series, using the name Bradford Scott. Interestingly, the Walt Slade yarns are seen by some as the precursor

to such graphically violent westerns as the Edge series by George G. Gilman, about whom we shall hear more in due course.

The pulps went into decline in the 1950s, although the western itself continued

to enjoy immense popularity. But now it moved at an even greater clip away from its melodramatic beginnings and started showing a greater maturity. Western characters and situations were no longer clear-cut. Now, when the hero stopped a bullet, it hurt like hell and bled like a bitch. He made mistakes just like everyone else, although things invariably came out all right in the end.

Among the authors who best handled this new slant on the Old West was Lewis B. Patten, a former auditor and rancher whose complex characters rarely found themselves involved in situations that were any simpler. The Trial of Judas Wiley , Red Runs the River , The Orphans of Coyote Creek and Death Rides A Black Horse are all superior examples of this newer, more realistic interpretation of frontier life. Wayne D Overholser, a school principal, teacher and then full-time writer from Oregon, was equally adept at the form, as indeed was the always-impressive and eminently collectible

Harry Whittington.

The British western was still as formulaic as its earliest American counterparts, however, with hackneyed plots, sham dialogue and cliched characters. But the market for westerns here in Britain was huge -- and publishers weren't slow to exploit it. Brown Watson started issuing western anthologies as early as 1948, and Scion Books eventually published more than 80 western paperbacks, including "oaters" by such cult favorites as Webb Anders, Jim Bowie (a pseudonym for the prolific Victor Norwood), John Russell Fearn and V Joseph Hanson. Incredibly, Hanson's westerns would continue to appear under both his own name and the pseudonym Jay Hill Potter for

the next fifty years.

Transworld Publishers began issuing books under its famous "Corgi" imprint in 1951, and among its first three titles was Jack Schaefer's classic Shane. For many years thereafter, Corgi could lay claim to one of the strongest western lists around, with a "corral" of writers like Ernest Haycox, E E Halleran,

Max Brand, William Hopson, Paul I Wellman,

Luke Short, Frank Gruber and L P Holmes.

Indeed, it was Corgi who really launched Louis L'Amour. L'Amour remains the most successful western writer of all time, with worldwide sales well in excess of 175 million copies. What is even more remarkable, however, is that his books weren't simply based on research. L'Amour's main source of inspiration was his own extraordinary life, during the course of which he sailed a dhow on the Red Sea, was shipwrecked in the West Indies, handled

elephants at a circus and fought as a light-heavyweight boxer, winning 51 of his 59 fights!

In 1958, Brown Watson launched its Long Loop

imprint, and went on to reprint many hardcover westerns by the likes of the prolific Irish writer Albert King, but there is no doubt that their most famous "son" was J T Edson.

Nottinghamshire-born J T Edson first started writing whilst

still at school, and entered a Brown Watson literary competition in 1960. When his novel Trail Boss took second prize, he was quick to follow up on his initial success and submitted two more manuscripts, The Hard Riders and The Texan. Right from

the start, Edson's westerns chronicled the exploits of "The Floating Outfit", a sort of mobile fighting force under the control of wheelchair-bound Ole Devil Hardin.

Corgi maintained a strong line of westerns throughout the 1960s,

reprinting many of the Hopalong Cassidy novels of Clarence E. Mulford and the Sudden westerns of Oliver Strange. Their only really serious rival in the western stakes was Hamilton & Co, later Panther Books, who issued some beautiful-looking

westerns throughout the 1950s and 60s. One of their best writers was Matt Chisholm (real name Peter C Watts), whose westerns were always distinguished by tremendous style and authenticity. If J T Edson was the most successful British western writer, then Matt Chisholm was certainly the most accomplished.

Australian publisher Cleveland was also quick to spot and exploit the popularity of the western, a genre which they continue to publish even today. Their most famous writer was Leonard F. Meares, best-known under his Marshall Grover pseudonym. For more details about Len's life and work, check out the separate page we have devoted to him.

Meares wrote more than 700 books all told, but he wasn't the only writer working flat-out for Cleveland. Keith Hetherington was another prolific contributor, as both Kirk Hamilton and Brett Waring -- and as you will see when you check out our Keith Hetherington page, his high-quality westerns are still being published today, under the Black

Horse Western banner of Robert Hale Limited, where he writes as Jake Douglas, Tyler Hatch, Clayton Nash and Hank J Kirby.

The most prolific of the many prolific writers working for Cleveland, however,

just had to be Paul Wheelahan. Under four pen names - Emerson Dodge, Brett McKinley, Ben Jefferson and E. Jefferson Clay -- he wrote close to 900 westerns, and later published some great

western fiction under his own name, here in the U.K.

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, however, a tougher, harsher, and altogether more violent portrait of life on the untamed frontier began to emerge. Finn Arnesen, a western expert and editor with the Norwegian publisher Bladkompaniet A/S, best sums up what the reader of the day had come to expect; "They want a modern, realistic story with a factual background, also with a bit of sex and a touch of brutality. They want a hero who may throw up after he has killed a

man, who is changed and brutalised by his own acts of violence. They want women of flesh and

blood, with sexual cravings. They want realism."

Arnesen was describing Morgan Kane and his shadowy, violent world. Kane was the creation of former bank employee Kjell Hallbing, writing as Louis Masterson. The series, about a hard-drinking, hard-living, guilt-ridden Texas Ranger (and later U S Marshal) was a phenomenal

success in Hallbing's native Norway, where he galloped through more than 80 way-above-average

adventures, beginning with Without Mercy in 1971. Kane proved to be such a compelling character

that he also made regular, shorter appearances in Arnesen's fortnightly Western magazine. At

his height, there were even Morgan Kane playing cards!

Corgi picked up the series in the early 1970s and eventually published 41 English translations. In Britain, Kane's adventures ended on a high note with the classic Killer

Kane, but he never really caught on as a character here in Britain, although Kjell Hallbing

remained one of Norway's best-selling authors, and continued to chronicle Kane's adventures

for several years thereafter.

To a certain extent, Morgan Kane's thunder was stolen by New English Library's Edge series, penned by the accomplished British writer Terry Harknett and published under the

pseudonym George G Gilman. These ultra-violent westerns featured a cold-blooded half-breed

whose wisecracks usually formed the punchline at the end of each chapter. Two companion series,

Adam Steele and The Undertaker, testified not only to Gilman/Harknett's dominance of the market,

but also to the popularity of this new breed of western adventure.

Publishers - being publishers - were quick to identify this new market, and almost overnight the likes of Frank O'Rourke, Clifton Adams and Jack Schaeffer were replaced by a string of Edge clones, some of them better but none more successful than the original, and all of them written by a group of British writers known as "Piccadilly Cowboys" (the tag being that the furthest

west they'd ever been was to Piccadilly - in London's West End). These writers were Laurence

James, Angus Wells and John Harvey.

In almost every case, and as with Edge himself, the principal character was pushed into his violent life by a burning desire for revenge. Jubal Cade, in the novels by Charles R Pike

(a pseudonym initially used by Harknett, then Angus Wells, with a one-off assist by Ken Bulmer)

was, as the front cover copy told us, "a man trained to heal, but born to kill." He spent most

of the subsequent titles searching for the man who killed his wife. The life of James A Muir?s

Breed (in reality Angus Wells again) was turned upside down when his parents were murdered.

Cuchillo Oro, the Apache of William M James (Harknett and Laurence James, later James and Harvey),

hunted the army officer who killed his wife and son and mutilated his right hand. Herne the Hunter,

in the books by John J McLaglen (James and Harvey) was a gunfighter who gave up the violent life

to marry and settle down, only to come out of retirement when a bunch of drunken railroad passengers

raped his wife, an act which drove her to commit suicide.

John Ryker, alias Gunslinger, turned out to be the gunsmith who unwittingly

sold the Deringer used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. When his ageing father was murdered in retaliation -- you guessed it - Ryker strapped on his Navy Colt and promptly killed the killers. Gunslinger was written by Charles C Garrett, alias James and Wells.

And so it went on. The four Americans in the Gringos series by J D Sandon (Wells and Harvey) and Hawk and Peacemaker, the characters created by Wells and Harvey under the name William S. Brady, all had their own reasons for being particularly murderous. Only Bodie the Stalker, by Neil Hunter (Mike Linaker) , John Harvey's Hart the Regulator and the Rails novels of Bart

Shane (Donald S Rowland) left out the almost obligatory origin story, although the central character

in each was no slouch when it came to killing.

Arguably the worst of the bunch was the mysterious, black-clad Crow, in the books by James W Marvin (Laurence James), who had a habit of using his shotgun on playful dogs, and stomping unfortunate lizards who just happened to be on the wrong rock at the wrong time. This kind of

thing wasn't really what the western was all about. It was gratuitous and frankly distasteful -

but it sold.

Perhaps even more worryingly was the fact that we Brits didn't care much for the adult westerns which became so prevalent in the 1970s. We had imported copies of Longarm, Renegade, Slocum and J D Hardin's Raider and Doc, but they all fell by the wayside, the victims of poor

sales. Apparently, we preferred to read about blood, guts and gore than some of life's, ah,

more pleasant pursuits.

The western sold in greater quantities throughout the decade than at any time before or since. But there was no real variety in the westerns that dominated the 1970s, and when one

series eventually fell out of favor, they all did.

The decline of the paperback western in Britain was abrupt and apparently final. Throughout the 1980s, British publishers seemed almost afraid to even consider the genre. Hamlyn gave Matt Chisholm the chance to resurrect his rake-hell hero, Rem McAllister, and to create a new

hero, Joe Blade, and Star Books created their Covered Wagon imprint in order to publish the Track

series by Samuel P Bishop (a pseudonym for Shaun Hutson), but sadly this sequence proved to be

just another Edge clone that was about ten years too late.

Luckily, the hardcover market told a different story. Robert Hale Limited had long published hardcover, dust jacketed westerns for the British library market. In 1986 the dust

jackets were replaced by laminated pictorial boards and the "Black Horse Western" was born.

In those early days, Hale published about six westerns every month. Today, they regularly issue

ten westerns a month.

And let us not forget Piccadilly Publishing, the ebook publisher operated by Mike Stotter and Ben Bridges. We regularly publish seven or eight westerns each month in digital format, and the success of our venture has shown beyond any doubt that the popularity of the western is still very much alive ... and long may this happy state of affairs continue!

The Union Pacific Story

The Ranch Story

The Empire Story

The Revenge Story

Custer's Last Stand

The Outlaw's Story

The Marshal's Story

I wonder why he never thought to add "The Woman's Story", or "The Indian's

Story"?

As you might imagine, writing for the pulps was a tough and demanding school where only the fittest survived. "I learned more about writing for the pulps than any other publication,"

Louis L'Amour later declared. "Their demand was for a no-nonsense type of writing, and if one made a living at it, there was no time for sitting about twiddling the thumbs."

The western pulps never really considered characterization especially

important. Indeed, the only three stories Max Brand ever had rejected were the ones in which he tried to develop his protagonists. But not all the stories of the period were without such depth, and this is a good place to pause a moment and take a closer look at three of the more influential western writers of the time.

Zane Grey began a life-long love affair with the great outdoors

at a very early age, and unlike the dime novelists of his youth, he actually researched his stories thoroughly. Unencumbered by strict deadlines, he was able to spend upwards of three months on every book he wrote -- hence his greater emphasis on character and character development. Although

he is considered somewhat dated today, I would still recommend 30,000

on the Hoof, an epic yarn which cannot fail to sweep the reader along.

Ernest Haycox grew up in the logging camps of Portland, Oregon, served with the National Guard on the Mexican border and later fought in France during World War I. He started writing whilst still at college and sold his first short story in 1921. Haycox developed quickly as a western writer, and his novels are remarkable primarily for their meticulous attention to plot and historical authenticity. Anyone who reads Man in the Saddle, Rim of the Desert, The Border Trumpet or Bugles in the Afternoon will quickly discover this author's obvious strengths for themselves.

In a career that spanned four decades, Illinois-born Luke Short

(real name Frederick Dilley Glidden) penned fifty top-notch westerns. A failed journalist, Short worked as a logger and archaeologist's assistant before turning his attention to western fiction. Good pacing, credible plots and original, believable characters distinguish his work, and among the best of it you will find such classics as Sunset Graze, Bold Rider and Ambush.

The western pulps also pioneered the continuing (or series) character, and nowhere was this more apparent than in Texas Rangers, every issue of which chronicled the adventures of Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield.

Hatfield's gun-swift escapades were penned by Jackson Cole,

which was actually a house-name behind which labored a whole team of writers. Alexander Leslie Scott is the writer most associated with the pseudonym. He started writing westerns whilst still in his early twenties, and tried whenever possible to base his plots upon his own first-hand experiences. A prolific penman, he also went on to compose about 125 stories in the Walt Slade series, using the name Bradford Scott. Interestingly, the Walt Slade yarns are seen by some as the precursor

to such graphically violent westerns as the Edge series by George G. Gilman, about whom we shall hear more in due course.

The pulps went into decline in the 1950s, although the western itself continued

to enjoy immense popularity. But now it moved at an even greater clip away from its melodramatic beginnings and started showing a greater maturity. Western characters and situations were no longer clear-cut. Now, when the hero stopped a bullet, it hurt like hell and bled like a bitch. He made mistakes just like everyone else, although things invariably came out all right in the end.

Among the authors who best handled this new slant on the Old West was Lewis B. Patten, a former auditor and rancher whose complex characters rarely found themselves involved in situations that were any simpler. The Trial of Judas Wiley , Red Runs the River , The Orphans of Coyote Creek and Death Rides A Black Horse are all superior examples of this newer, more realistic interpretation of frontier life. Wayne D Overholser, a school principal, teacher and then full-time writer from Oregon, was equally adept at the form, as indeed was the always-impressive and eminently collectible

Harry Whittington.

The British western was still as formulaic as its earliest American counterparts, however, with hackneyed plots, sham dialogue and cliched characters. But the market for westerns here in Britain was huge -- and publishers weren't slow to exploit it. Brown Watson started issuing western anthologies as early as 1948, and Scion Books eventually published more than 80 western paperbacks, including "oaters" by such cult favorites as Webb Anders, Jim Bowie (a pseudonym for the prolific Victor Norwood), John Russell Fearn and V Joseph Hanson. Incredibly, Hanson's westerns would continue to appear under both his own name and the pseudonym Jay Hill Potter for

the next fifty years.

Transworld Publishers began issuing books under its famous "Corgi" imprint in 1951, and among its first three titles was Jack Schaefer's classic Shane. For many years thereafter, Corgi could lay claim to one of the strongest western lists around, with a "corral" of writers like Ernest Haycox, E E Halleran,

Max Brand, William Hopson, Paul I Wellman,

Luke Short, Frank Gruber and L P Holmes.

Indeed, it was Corgi who really launched Louis L'Amour. L'Amour remains the most successful western writer of all time, with worldwide sales well in excess of 175 million copies. What is even more remarkable, however, is that his books weren't simply based on research. L'Amour's main source of inspiration was his own extraordinary life, during the course of which he sailed a dhow on the Red Sea, was shipwrecked in the West Indies, handled

elephants at a circus and fought as a light-heavyweight boxer, winning 51 of his 59 fights!

In 1958, Brown Watson launched its Long Loop

imprint, and went on to reprint many hardcover westerns by the likes of the prolific Irish writer Albert King, but there is no doubt that their most famous "son" was J T Edson.

Nottinghamshire-born J T Edson first started writing whilst

still at school, and entered a Brown Watson literary competition in 1960. When his novel Trail Boss took second prize, he was quick to follow up on his initial success and submitted two more manuscripts, The Hard Riders and The Texan. Right from

the start, Edson's westerns chronicled the exploits of "The Floating Outfit", a sort of mobile fighting force under the control of wheelchair-bound Ole Devil Hardin.

Corgi maintained a strong line of westerns throughout the 1960s,

reprinting many of the Hopalong Cassidy novels of Clarence E. Mulford and the Sudden westerns of Oliver Strange. Their only really serious rival in the western stakes was Hamilton & Co, later Panther Books, who issued some beautiful-looking

westerns throughout the 1950s and 60s. One of their best writers was Matt Chisholm (real name Peter C Watts), whose westerns were always distinguished by tremendous style and authenticity. If J T Edson was the most successful British western writer, then Matt Chisholm was certainly the most accomplished.

Australian publisher Cleveland was also quick to spot and exploit the popularity of the western, a genre which they continue to publish even today. Their most famous writer was Leonard F. Meares, best-known under his Marshall Grover pseudonym. For more details about Len's life and work, check out the separate page we have devoted to him.

Meares wrote more than 700 books all told, but he wasn't the only writer working flat-out for Cleveland. Keith Hetherington was another prolific contributor, as both Kirk Hamilton and Brett Waring -- and as you will see when you check out our Keith Hetherington page, his high-quality westerns are still being published today, under the Black

Horse Western banner of Robert Hale Limited, where he writes as Jake Douglas, Tyler Hatch, Clayton Nash and Hank J Kirby.

The most prolific of the many prolific writers working for Cleveland, however,

just had to be Paul Wheelahan. Under four pen names - Emerson Dodge, Brett McKinley, Ben Jefferson and E. Jefferson Clay -- he wrote close to 900 westerns, and later published some great

western fiction under his own name, here in the U.K.

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, however, a tougher, harsher, and altogether more violent portrait of life on the untamed frontier began to emerge. Finn Arnesen, a western expert and editor with the Norwegian publisher Bladkompaniet A/S, best sums up what the reader of the day had come to expect; "They want a modern, realistic story with a factual background, also with a bit of sex and a touch of brutality. They want a hero who may throw up after he has killed a

man, who is changed and brutalised by his own acts of violence. They want women of flesh and

blood, with sexual cravings. They want realism."

Arnesen was describing Morgan Kane and his shadowy, violent world. Kane was the creation of former bank employee Kjell Hallbing, writing as Louis Masterson. The series, about a hard-drinking, hard-living, guilt-ridden Texas Ranger (and later U S Marshal) was a phenomenal

success in Hallbing's native Norway, where he galloped through more than 80 way-above-average

adventures, beginning with Without Mercy in 1971. Kane proved to be such a compelling character

that he also made regular, shorter appearances in Arnesen's fortnightly Western magazine. At

his height, there were even Morgan Kane playing cards!

Corgi picked up the series in the early 1970s and eventually published 41 English translations. In Britain, Kane's adventures ended on a high note with the classic Killer

Kane, but he never really caught on as a character here in Britain, although Kjell Hallbing

remained one of Norway's best-selling authors, and continued to chronicle Kane's adventures

for several years thereafter.

To a certain extent, Morgan Kane's thunder was stolen by New English Library's Edge series, penned by the accomplished British writer Terry Harknett and published under the

pseudonym George G Gilman. These ultra-violent westerns featured a cold-blooded half-breed

whose wisecracks usually formed the punchline at the end of each chapter. Two companion series,

Adam Steele and The Undertaker, testified not only to Gilman/Harknett's dominance of the market,

but also to the popularity of this new breed of western adventure.

Publishers - being publishers - were quick to identify this new market, and almost overnight the likes of Frank O'Rourke, Clifton Adams and Jack Schaeffer were replaced by a string of Edge clones, some of them better but none more successful than the original, and all of them written by a group of British writers known as "Piccadilly Cowboys" (the tag being that the furthest

west they'd ever been was to Piccadilly - in London's West End). These writers were Laurence

James, Angus Wells and John Harvey.

In almost every case, and as with Edge himself, the principal character was pushed into his violent life by a burning desire for revenge. Jubal Cade, in the novels by Charles R Pike

(a pseudonym initially used by Harknett, then Angus Wells, with a one-off assist by Ken Bulmer)

was, as the front cover copy told us, "a man trained to heal, but born to kill." He spent most

of the subsequent titles searching for the man who killed his wife. The life of James A Muir?s

Breed (in reality Angus Wells again) was turned upside down when his parents were murdered.

Cuchillo Oro, the Apache of William M James (Harknett and Laurence James, later James and Harvey),

hunted the army officer who killed his wife and son and mutilated his right hand. Herne the Hunter,

in the books by John J McLaglen (James and Harvey) was a gunfighter who gave up the violent life

to marry and settle down, only to come out of retirement when a bunch of drunken railroad passengers

raped his wife, an act which drove her to commit suicide.

John Ryker, alias Gunslinger, turned out to be the gunsmith who unwittingly

sold the Deringer used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. When his ageing father was murdered in retaliation -- you guessed it - Ryker strapped on his Navy Colt and promptly killed the killers. Gunslinger was written by Charles C Garrett, alias James and Wells.

And so it went on. The four Americans in the Gringos series by J D Sandon (Wells and Harvey) and Hawk and Peacemaker, the characters created by Wells and Harvey under the name William S. Brady, all had their own reasons for being particularly murderous. Only Bodie the Stalker, by Neil Hunter (Mike Linaker) , John Harvey's Hart the Regulator and the Rails novels of Bart

Shane (Donald S Rowland) left out the almost obligatory origin story, although the central character

in each was no slouch when it came to killing.

Arguably the worst of the bunch was the mysterious, black-clad Crow, in the books by James W Marvin (Laurence James), who had a habit of using his shotgun on playful dogs, and stomping unfortunate lizards who just happened to be on the wrong rock at the wrong time. This kind of

thing wasn't really what the western was all about. It was gratuitous and frankly distasteful -

but it sold.

Perhaps even more worryingly was the fact that we Brits didn't care much for the adult westerns which became so prevalent in the 1970s. We had imported copies of Longarm, Renegade, Slocum and J D Hardin's Raider and Doc, but they all fell by the wayside, the victims of poor

sales. Apparently, we preferred to read about blood, guts and gore than some of life's, ah,

more pleasant pursuits.

The western sold in greater quantities throughout the decade than at any time before or since. But there was no real variety in the westerns that dominated the 1970s, and when one

series eventually fell out of favor, they all did.

The decline of the paperback western in Britain was abrupt and apparently final. Throughout the 1980s, British publishers seemed almost afraid to even consider the genre. Hamlyn gave Matt Chisholm the chance to resurrect his rake-hell hero, Rem McAllister, and to create a new

hero, Joe Blade, and Star Books created their Covered Wagon imprint in order to publish the Track

series by Samuel P Bishop (a pseudonym for Shaun Hutson), but sadly this sequence proved to be

just another Edge clone that was about ten years too late.

Luckily, the hardcover market told a different story. Robert Hale Limited had long published hardcover, dust jacketed westerns for the British library market. In 1986 the dust

jackets were replaced by laminated pictorial boards and the "Black Horse Western" was born.

In those early days, Hale published about six westerns every month. Today, they regularly issue

ten westerns a month.

And let us not forget Piccadilly Publishing, the ebook publisher operated by Mike Stotter and Ben Bridges. We regularly publish seven or eight westerns each month in digital format, and the success of our venture has shown beyond any doubt that the popularity of the western is still very much alive ... and long may this happy state of affairs continue!

The Ranch Story

The Empire Story

The Revenge Story

Custer's Last Stand

The Outlaw's Story

The Marshal's Story

I wonder why he never thought to add "The Woman's Story", or "The Indian's

Story"?

As you might imagine, writing for the pulps was a tough and demanding school where only the fittest survived. "I learned more about writing for the pulps than any other publication,"

Louis L'Amour later declared. "Their demand was for a no-nonsense type of writing, and if one made a living at it, there was no time for sitting about twiddling the thumbs."

The western pulps never really considered characterization especially

important. Indeed, the only three stories Max Brand ever had rejected were the ones in which he tried to develop his protagonists. But not all the stories of the period were without such depth, and this is a good place to pause a moment and take a closer look at three of the more influential western writers of the time.

Zane Grey began a life-long love affair with the great outdoors

at a very early age, and unlike the dime novelists of his youth, he actually researched his stories thoroughly. Unencumbered by strict deadlines, he was able to spend upwards of three months on every book he wrote -- hence his greater emphasis on character and character development. Although

he is considered somewhat dated today, I would still recommend 30,000

on the Hoof, an epic yarn which cannot fail to sweep the reader along.

Ernest Haycox grew up in the logging camps of Portland, Oregon, served with the National Guard on the Mexican border and later fought in France during World War I. He started writing whilst still at college and sold his first short story in 1921. Haycox developed quickly as a western writer, and his novels are remarkable primarily for their meticulous attention to plot and historical authenticity. Anyone who reads Man in the Saddle, Rim of the Desert, The Border Trumpet or Bugles in the Afternoon will quickly discover this author's obvious strengths for themselves.

In a career that spanned four decades, Illinois-born Luke Short

(real name Frederick Dilley Glidden) penned fifty top-notch westerns. A failed journalist, Short worked as a logger and archaeologist's assistant before turning his attention to western fiction. Good pacing, credible plots and original, believable characters distinguish his work, and among the best of it you will find such classics as Sunset Graze, Bold Rider and Ambush.

The western pulps also pioneered the continuing (or series) character, and nowhere was this more apparent than in Texas Rangers, every issue of which chronicled the adventures of Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield.

Hatfield's gun-swift escapades were penned by Jackson Cole,

which was actually a house-name behind which labored a whole team of writers. Alexander Leslie Scott is the writer most associated with the pseudonym. He started writing westerns whilst still in his early twenties, and tried whenever possible to base his plots upon his own first-hand experiences. A prolific penman, he also went on to compose about 125 stories in the Walt Slade series, using the name Bradford Scott. Interestingly, the Walt Slade yarns are seen by some as the precursor

to such graphically violent westerns as the Edge series by George G. Gilman, about whom we shall hear more in due course.

The pulps went into decline in the 1950s, although the western itself continued

to enjoy immense popularity. But now it moved at an even greater clip away from its melodramatic beginnings and started showing a greater maturity. Western characters and situations were no longer clear-cut. Now, when the hero stopped a bullet, it hurt like hell and bled like a bitch. He made mistakes just like everyone else, although things invariably came out all right in the end.

Among the authors who best handled this new slant on the Old West was Lewis B. Patten, a former auditor and rancher whose complex characters rarely found themselves involved in situations that were any simpler. The Trial of Judas Wiley , Red Runs the River , The Orphans of Coyote Creek and Death Rides A Black Horse are all superior examples of this newer, more realistic interpretation of frontier life. Wayne D Overholser, a school principal, teacher and then full-time writer from Oregon, was equally adept at the form, as indeed was the always-impressive and eminently collectible

Harry Whittington.

The British western was still as formulaic as its earliest American counterparts, however, with hackneyed plots, sham dialogue and cliched characters. But the market for westerns here in Britain was huge -- and publishers weren't slow to exploit it. Brown Watson started issuing western anthologies as early as 1948, and Scion Books eventually published more than 80 western paperbacks, including "oaters" by such cult favorites as Webb Anders, Jim Bowie (a pseudonym for the prolific Victor Norwood), John Russell Fearn and V Joseph Hanson. Incredibly, Hanson's westerns would continue to appear under both his own name and the pseudonym Jay Hill Potter for

the next fifty years.

Transworld Publishers began issuing books under its famous "Corgi" imprint in 1951, and among its first three titles was Jack Schaefer's classic Shane. For many years thereafter, Corgi could lay claim to one of the strongest western lists around, with a "corral" of writers like Ernest Haycox, E E Halleran,

Max Brand, William Hopson, Paul I Wellman,

Luke Short, Frank Gruber and L P Holmes.

Indeed, it was Corgi who really launched Louis L'Amour. L'Amour remains the most successful western writer of all time, with worldwide sales well in excess of 175 million copies. What is even more remarkable, however, is that his books weren't simply based on research. L'Amour's main source of inspiration was his own extraordinary life, during the course of which he sailed a dhow on the Red Sea, was shipwrecked in the West Indies, handled

elephants at a circus and fought as a light-heavyweight boxer, winning 51 of his 59 fights!

In 1958, Brown Watson launched its Long Loop

imprint, and went on to reprint many hardcover westerns by the likes of the prolific Irish writer Albert King, but there is no doubt that their most famous "son" was J T Edson.

Nottinghamshire-born J T Edson first started writing whilst

still at school, and entered a Brown Watson literary competition in 1960. When his novel Trail Boss took second prize, he was quick to follow up on his initial success and submitted two more manuscripts, The Hard Riders and The Texan. Right from

the start, Edson's westerns chronicled the exploits of "The Floating Outfit", a sort of mobile fighting force under the control of wheelchair-bound Ole Devil Hardin.

Corgi maintained a strong line of westerns throughout the 1960s,

reprinting many of the Hopalong Cassidy novels of Clarence E. Mulford and the Sudden westerns of Oliver Strange. Their only really serious rival in the western stakes was Hamilton & Co, later Panther Books, who issued some beautiful-looking

westerns throughout the 1950s and 60s. One of their best writers was Matt Chisholm (real name Peter C Watts), whose westerns were always distinguished by tremendous style and authenticity. If J T Edson was the most successful British western writer, then Matt Chisholm was certainly the most accomplished.

Australian publisher Cleveland was also quick to spot and exploit the popularity of the western, a genre which they continue to publish even today. Their most famous writer was Leonard F. Meares, best-known under his Marshall Grover pseudonym. For more details about Len's life and work, check out the separate page we have devoted to him.

Meares wrote more than 700 books all told, but he wasn't the only writer working flat-out for Cleveland. Keith Hetherington was another prolific contributor, as both Kirk Hamilton and Brett Waring -- and as you will see when you check out our Keith Hetherington page, his high-quality westerns are still being published today, under the Black

Horse Western banner of Robert Hale Limited, where he writes as Jake Douglas, Tyler Hatch, Clayton Nash and Hank J Kirby.

The most prolific of the many prolific writers working for Cleveland, however,

just had to be Paul Wheelahan. Under four pen names - Emerson Dodge, Brett McKinley, Ben Jefferson and E. Jefferson Clay -- he wrote close to 900 westerns, and later published some great

western fiction under his own name, here in the U.K.

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, however, a tougher, harsher, and altogether more violent portrait of life on the untamed frontier began to emerge. Finn Arnesen, a western expert and editor with the Norwegian publisher Bladkompaniet A/S, best sums up what the reader of the day had come to expect; "They want a modern, realistic story with a factual background, also with a bit of sex and a touch of brutality. They want a hero who may throw up after he has killed a

man, who is changed and brutalised by his own acts of violence. They want women of flesh and

blood, with sexual cravings. They want realism."

Arnesen was describing Morgan Kane and his shadowy, violent world. Kane was the creation of former bank employee Kjell Hallbing, writing as Louis Masterson. The series, about a hard-drinking, hard-living, guilt-ridden Texas Ranger (and later U S Marshal) was a phenomenal

success in Hallbing's native Norway, where he galloped through more than 80 way-above-average

adventures, beginning with Without Mercy in 1971. Kane proved to be such a compelling character

that he also made regular, shorter appearances in Arnesen's fortnightly Western magazine. At

his height, there were even Morgan Kane playing cards!

Corgi picked up the series in the early 1970s and eventually published 41 English translations. In Britain, Kane's adventures ended on a high note with the classic Killer

Kane, but he never really caught on as a character here in Britain, although Kjell Hallbing

remained one of Norway's best-selling authors, and continued to chronicle Kane's adventures

for several years thereafter.

To a certain extent, Morgan Kane's thunder was stolen by New English Library's Edge series, penned by the accomplished British writer Terry Harknett and published under the

pseudonym George G Gilman. These ultra-violent westerns featured a cold-blooded half-breed

whose wisecracks usually formed the punchline at the end of each chapter. Two companion series,

Adam Steele and The Undertaker, testified not only to Gilman/Harknett's dominance of the market,

but also to the popularity of this new breed of western adventure.

Publishers - being publishers - were quick to identify this new market, and almost overnight the likes of Frank O'Rourke, Clifton Adams and Jack Schaeffer were replaced by a string of Edge clones, some of them better but none more successful than the original, and all of them written by a group of British writers known as "Piccadilly Cowboys" (the tag being that the furthest

west they'd ever been was to Piccadilly - in London's West End). These writers were Laurence

James, Angus Wells and John Harvey.

In almost every case, and as with Edge himself, the principal character was pushed into his violent life by a burning desire for revenge. Jubal Cade, in the novels by Charles R Pike

(a pseudonym initially used by Harknett, then Angus Wells, with a one-off assist by Ken Bulmer)

was, as the front cover copy told us, "a man trained to heal, but born to kill." He spent most

of the subsequent titles searching for the man who killed his wife. The life of James A Muir?s

Breed (in reality Angus Wells again) was turned upside down when his parents were murdered.

Cuchillo Oro, the Apache of William M James (Harknett and Laurence James, later James and Harvey),

hunted the army officer who killed his wife and son and mutilated his right hand. Herne the Hunter,

in the books by John J McLaglen (James and Harvey) was a gunfighter who gave up the violent life

to marry and settle down, only to come out of retirement when a bunch of drunken railroad passengers

raped his wife, an act which drove her to commit suicide.

John Ryker, alias Gunslinger, turned out to be the gunsmith who unwittingly

sold the Deringer used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. When his ageing father was murdered in retaliation -- you guessed it - Ryker strapped on his Navy Colt and promptly killed the killers. Gunslinger was written by Charles C Garrett, alias James and Wells.

And so it went on. The four Americans in the Gringos series by J D Sandon (Wells and Harvey) and Hawk and Peacemaker, the characters created by Wells and Harvey under the name William S. Brady, all had their own reasons for being particularly murderous. Only Bodie the Stalker, by Neil Hunter (Mike Linaker) , John Harvey's Hart the Regulator and the Rails novels of Bart

Shane (Donald S Rowland) left out the almost obligatory origin story, although the central character

in each was no slouch when it came to killing.

Arguably the worst of the bunch was the mysterious, black-clad Crow, in the books by James W Marvin (Laurence James), who had a habit of using his shotgun on playful dogs, and stomping unfortunate lizards who just happened to be on the wrong rock at the wrong time. This kind of

thing wasn't really what the western was all about. It was gratuitous and frankly distasteful -

but it sold.

Perhaps even more worryingly was the fact that we Brits didn't care much for the adult westerns which became so prevalent in the 1970s. We had imported copies of Longarm, Renegade, Slocum and J D Hardin's Raider and Doc, but they all fell by the wayside, the victims of poor

sales. Apparently, we preferred to read about blood, guts and gore than some of life's, ah,

more pleasant pursuits.

The western sold in greater quantities throughout the decade than at any time before or since. But there was no real variety in the westerns that dominated the 1970s, and when one

series eventually fell out of favor, they all did.

The decline of the paperback western in Britain was abrupt and apparently final. Throughout the 1980s, British publishers seemed almost afraid to even consider the genre. Hamlyn gave Matt Chisholm the chance to resurrect his rake-hell hero, Rem McAllister, and to create a new

hero, Joe Blade, and Star Books created their Covered Wagon imprint in order to publish the Track

series by Samuel P Bishop (a pseudonym for Shaun Hutson), but sadly this sequence proved to be

just another Edge clone that was about ten years too late.

Luckily, the hardcover market told a different story. Robert Hale Limited had long published hardcover, dust jacketed westerns for the British library market. In 1986 the dust

jackets were replaced by laminated pictorial boards and the "Black Horse Western" was born.

In those early days, Hale published about six westerns every month. Today, they regularly issue

ten westerns a month.

And let us not forget Piccadilly Publishing, the ebook publisher operated by Mike Stotter and Ben Bridges. We regularly publish seven or eight westerns each month in digital format, and the success of our venture has shown beyond any doubt that the popularity of the western is still very much alive ... and long may this happy state of affairs continue!

The Empire Story

The Revenge Story

Custer's Last Stand

The Outlaw's Story

The Marshal's Story

I wonder why he never thought to add "The Woman's Story", or "The Indian's

Story"?

As you might imagine, writing for the pulps was a tough and demanding school where only the fittest survived. "I learned more about writing for the pulps than any other publication,"

Louis L'Amour later declared. "Their demand was for a no-nonsense type of writing, and if one made a living at it, there was no time for sitting about twiddling the thumbs."

The western pulps never really considered characterization especially

important. Indeed, the only three stories Max Brand ever had rejected were the ones in which he tried to develop his protagonists. But not all the stories of the period were without such depth, and this is a good place to pause a moment and take a closer look at three of the more influential western writers of the time.

Zane Grey began a life-long love affair with the great outdoors

at a very early age, and unlike the dime novelists of his youth, he actually researched his stories thoroughly. Unencumbered by strict deadlines, he was able to spend upwards of three months on every book he wrote -- hence his greater emphasis on character and character development. Although

he is considered somewhat dated today, I would still recommend 30,000

on the Hoof, an epic yarn which cannot fail to sweep the reader along.

Ernest Haycox grew up in the logging camps of Portland, Oregon, served with the National Guard on the Mexican border and later fought in France during World War I. He started writing whilst still at college and sold his first short story in 1921. Haycox developed quickly as a western writer, and his novels are remarkable primarily for their meticulous attention to plot and historical authenticity. Anyone who reads Man in the Saddle, Rim of the Desert, The Border Trumpet or Bugles in the Afternoon will quickly discover this author's obvious strengths for themselves.

In a career that spanned four decades, Illinois-born Luke Short

(real name Frederick Dilley Glidden) penned fifty top-notch westerns. A failed journalist, Short worked as a logger and archaeologist's assistant before turning his attention to western fiction. Good pacing, credible plots and original, believable characters distinguish his work, and among the best of it you will find such classics as Sunset Graze, Bold Rider and Ambush.

The western pulps also pioneered the continuing (or series) character, and nowhere was this more apparent than in Texas Rangers, every issue of which chronicled the adventures of Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield.

Hatfield's gun-swift escapades were penned by Jackson Cole,

which was actually a house-name behind which labored a whole team of writers. Alexander Leslie Scott is the writer most associated with the pseudonym. He started writing westerns whilst still in his early twenties, and tried whenever possible to base his plots upon his own first-hand experiences. A prolific penman, he also went on to compose about 125 stories in the Walt Slade series, using the name Bradford Scott. Interestingly, the Walt Slade yarns are seen by some as the precursor

to such graphically violent westerns as the Edge series by George G. Gilman, about whom we shall hear more in due course.

The pulps went into decline in the 1950s, although the western itself continued

to enjoy immense popularity. But now it moved at an even greater clip away from its melodramatic beginnings and started showing a greater maturity. Western characters and situations were no longer clear-cut. Now, when the hero stopped a bullet, it hurt like hell and bled like a bitch. He made mistakes just like everyone else, although things invariably came out all right in the end.

Among the authors who best handled this new slant on the Old West was Lewis B. Patten, a former auditor and rancher whose complex characters rarely found themselves involved in situations that were any simpler. The Trial of Judas Wiley , Red Runs the River , The Orphans of Coyote Creek and Death Rides A Black Horse are all superior examples of this newer, more realistic interpretation of frontier life. Wayne D Overholser, a school principal, teacher and then full-time writer from Oregon, was equally adept at the form, as indeed was the always-impressive and eminently collectible

Harry Whittington.

The British western was still as formulaic as its earliest American counterparts, however, with hackneyed plots, sham dialogue and cliched characters. But the market for westerns here in Britain was huge -- and publishers weren't slow to exploit it. Brown Watson started issuing western anthologies as early as 1948, and Scion Books eventually published more than 80 western paperbacks, including "oaters" by such cult favorites as Webb Anders, Jim Bowie (a pseudonym for the prolific Victor Norwood), John Russell Fearn and V Joseph Hanson. Incredibly, Hanson's westerns would continue to appear under both his own name and the pseudonym Jay Hill Potter for

the next fifty years.

Transworld Publishers began issuing books under its famous "Corgi" imprint in 1951, and among its first three titles was Jack Schaefer's classic Shane. For many years thereafter, Corgi could lay claim to one of the strongest western lists around, with a "corral" of writers like Ernest Haycox, E E Halleran,

Max Brand, William Hopson, Paul I Wellman,

Luke Short, Frank Gruber and L P Holmes.

Indeed, it was Corgi who really launched Louis L'Amour. L'Amour remains the most successful western writer of all time, with worldwide sales well in excess of 175 million copies. What is even more remarkable, however, is that his books weren't simply based on research. L'Amour's main source of inspiration was his own extraordinary life, during the course of which he sailed a dhow on the Red Sea, was shipwrecked in the West Indies, handled

elephants at a circus and fought as a light-heavyweight boxer, winning 51 of his 59 fights!

In 1958, Brown Watson launched its Long Loop

imprint, and went on to reprint many hardcover westerns by the likes of the prolific Irish writer Albert King, but there is no doubt that their most famous "son" was J T Edson.

Nottinghamshire-born J T Edson first started writing whilst

still at school, and entered a Brown Watson literary competition in 1960. When his novel Trail Boss took second prize, he was quick to follow up on his initial success and submitted two more manuscripts, The Hard Riders and The Texan. Right from

the start, Edson's westerns chronicled the exploits of "The Floating Outfit", a sort of mobile fighting force under the control of wheelchair-bound Ole Devil Hardin.

Corgi maintained a strong line of westerns throughout the 1960s,

reprinting many of the Hopalong Cassidy novels of Clarence E. Mulford and the Sudden westerns of Oliver Strange. Their only really serious rival in the western stakes was Hamilton & Co, later Panther Books, who issued some beautiful-looking

westerns throughout the 1950s and 60s. One of their best writers was Matt Chisholm (real name Peter C Watts), whose westerns were always distinguished by tremendous style and authenticity. If J T Edson was the most successful British western writer, then Matt Chisholm was certainly the most accomplished.

Australian publisher Cleveland was also quick to spot and exploit the popularity of the western, a genre which they continue to publish even today. Their most famous writer was Leonard F. Meares, best-known under his Marshall Grover pseudonym. For more details about Len's life and work, check out the separate page we have devoted to him.

Meares wrote more than 700 books all told, but he wasn't the only writer working flat-out for Cleveland. Keith Hetherington was another prolific contributor, as both Kirk Hamilton and Brett Waring -- and as you will see when you check out our Keith Hetherington page, his high-quality westerns are still being published today, under the Black

Horse Western banner of Robert Hale Limited, where he writes as Jake Douglas, Tyler Hatch, Clayton Nash and Hank J Kirby.

The most prolific of the many prolific writers working for Cleveland, however,

just had to be Paul Wheelahan. Under four pen names - Emerson Dodge, Brett McKinley, Ben Jefferson and E. Jefferson Clay -- he wrote close to 900 westerns, and later published some great

western fiction under his own name, here in the U.K.

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, however, a tougher, harsher, and altogether more violent portrait of life on the untamed frontier began to emerge. Finn Arnesen, a western expert and editor with the Norwegian publisher Bladkompaniet A/S, best sums up what the reader of the day had come to expect; "They want a modern, realistic story with a factual background, also with a bit of sex and a touch of brutality. They want a hero who may throw up after he has killed a

man, who is changed and brutalised by his own acts of violence. They want women of flesh and

blood, with sexual cravings. They want realism."

Arnesen was describing Morgan Kane and his shadowy, violent world. Kane was the creation of former bank employee Kjell Hallbing, writing as Louis Masterson. The series, about a hard-drinking, hard-living, guilt-ridden Texas Ranger (and later U S Marshal) was a phenomenal

success in Hallbing's native Norway, where he galloped through more than 80 way-above-average

adventures, beginning with Without Mercy in 1971. Kane proved to be such a compelling character

that he also made regular, shorter appearances in Arnesen's fortnightly Western magazine. At

his height, there were even Morgan Kane playing cards!

Corgi picked up the series in the early 1970s and eventually published 41 English translations. In Britain, Kane's adventures ended on a high note with the classic Killer

Kane, but he never really caught on as a character here in Britain, although Kjell Hallbing

remained one of Norway's best-selling authors, and continued to chronicle Kane's adventures

for several years thereafter.

To a certain extent, Morgan Kane's thunder was stolen by New English Library's Edge series, penned by the accomplished British writer Terry Harknett and published under the

pseudonym George G Gilman. These ultra-violent westerns featured a cold-blooded half-breed

whose wisecracks usually formed the punchline at the end of each chapter. Two companion series,

Adam Steele and The Undertaker, testified not only to Gilman/Harknett's dominance of the market,

but also to the popularity of this new breed of western adventure.

Publishers - being publishers - were quick to identify this new market, and almost overnight the likes of Frank O'Rourke, Clifton Adams and Jack Schaeffer were replaced by a string of Edge clones, some of them better but none more successful than the original, and all of them written by a group of British writers known as "Piccadilly Cowboys" (the tag being that the furthest

west they'd ever been was to Piccadilly - in London's West End). These writers were Laurence

James, Angus Wells and John Harvey.

In almost every case, and as with Edge himself, the principal character was pushed into his violent life by a burning desire for revenge. Jubal Cade, in the novels by Charles R Pike

(a pseudonym initially used by Harknett, then Angus Wells, with a one-off assist by Ken Bulmer)

was, as the front cover copy told us, "a man trained to heal, but born to kill." He spent most

of the subsequent titles searching for the man who killed his wife. The life of James A Muir?s

Breed (in reality Angus Wells again) was turned upside down when his parents were murdered.

Cuchillo Oro, the Apache of William M James (Harknett and Laurence James, later James and Harvey),

hunted the army officer who killed his wife and son and mutilated his right hand. Herne the Hunter,

in the books by John J McLaglen (James and Harvey) was a gunfighter who gave up the violent life

to marry and settle down, only to come out of retirement when a bunch of drunken railroad passengers

raped his wife, an act which drove her to commit suicide.

John Ryker, alias Gunslinger, turned out to be the gunsmith who unwittingly

sold the Deringer used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. When his ageing father was murdered in retaliation -- you guessed it - Ryker strapped on his Navy Colt and promptly killed the killers. Gunslinger was written by Charles C Garrett, alias James and Wells.

And so it went on. The four Americans in the Gringos series by J D Sandon (Wells and Harvey) and Hawk and Peacemaker, the characters created by Wells and Harvey under the name William S. Brady, all had their own reasons for being particularly murderous. Only Bodie the Stalker, by Neil Hunter (Mike Linaker) , John Harvey's Hart the Regulator and the Rails novels of Bart

Shane (Donald S Rowland) left out the almost obligatory origin story, although the central character

in each was no slouch when it came to killing.

Arguably the worst of the bunch was the mysterious, black-clad Crow, in the books by James W Marvin (Laurence James), who had a habit of using his shotgun on playful dogs, and stomping unfortunate lizards who just happened to be on the wrong rock at the wrong time. This kind of

thing wasn't really what the western was all about. It was gratuitous and frankly distasteful -

but it sold.

Perhaps even more worryingly was the fact that we Brits didn't care much for the adult westerns which became so prevalent in the 1970s. We had imported copies of Longarm, Renegade, Slocum and J D Hardin's Raider and Doc, but they all fell by the wayside, the victims of poor

sales. Apparently, we preferred to read about blood, guts and gore than some of life's, ah,

more pleasant pursuits.

The western sold in greater quantities throughout the decade than at any time before or since. But there was no real variety in the westerns that dominated the 1970s, and when one

series eventually fell out of favor, they all did.

The decline of the paperback western in Britain was abrupt and apparently final. Throughout the 1980s, British publishers seemed almost afraid to even consider the genre. Hamlyn gave Matt Chisholm the chance to resurrect his rake-hell hero, Rem McAllister, and to create a new

hero, Joe Blade, and Star Books created their Covered Wagon imprint in order to publish the Track

series by Samuel P Bishop (a pseudonym for Shaun Hutson), but sadly this sequence proved to be

just another Edge clone that was about ten years too late.

Luckily, the hardcover market told a different story. Robert Hale Limited had long published hardcover, dust jacketed westerns for the British library market. In 1986 the dust

jackets were replaced by laminated pictorial boards and the "Black Horse Western" was born.

In those early days, Hale published about six westerns every month. Today, they regularly issue

ten westerns a month.

And let us not forget Piccadilly Publishing, the ebook publisher operated by Mike Stotter and Ben Bridges. We regularly publish seven or eight westerns each month in digital format, and the success of our venture has shown beyond any doubt that the popularity of the western is still very much alive ... and long may this happy state of affairs continue!

The Revenge Story

Custer's Last Stand

The Outlaw's Story

The Marshal's Story

I wonder why he never thought to add "The Woman's Story", or "The Indian's

Story"?

As you might imagine, writing for the pulps was a tough and demanding school where only the fittest survived. "I learned more about writing for the pulps than any other publication,"

Louis L'Amour later declared. "Their demand was for a no-nonsense type of writing, and if one made a living at it, there was no time for sitting about twiddling the thumbs."

The western pulps never really considered characterization especially

important. Indeed, the only three stories Max Brand ever had rejected were the ones in which he tried to develop his protagonists. But not all the stories of the period were without such depth, and this is a good place to pause a moment and take a closer look at three of the more influential western writers of the time.

Zane Grey began a life-long love affair with the great outdoors

at a very early age, and unlike the dime novelists of his youth, he actually researched his stories thoroughly. Unencumbered by strict deadlines, he was able to spend upwards of three months on every book he wrote -- hence his greater emphasis on character and character development. Although

he is considered somewhat dated today, I would still recommend 30,000

on the Hoof, an epic yarn which cannot fail to sweep the reader along.

Ernest Haycox grew up in the logging camps of Portland, Oregon, served with the National Guard on the Mexican border and later fought in France during World War I. He started writing whilst still at college and sold his first short story in 1921. Haycox developed quickly as a western writer, and his novels are remarkable primarily for their meticulous attention to plot and historical authenticity. Anyone who reads Man in the Saddle, Rim of the Desert, The Border Trumpet or Bugles in the Afternoon will quickly discover this author's obvious strengths for themselves.

In a career that spanned four decades, Illinois-born Luke Short

(real name Frederick Dilley Glidden) penned fifty top-notch westerns. A failed journalist, Short worked as a logger and archaeologist's assistant before turning his attention to western fiction. Good pacing, credible plots and original, believable characters distinguish his work, and among the best of it you will find such classics as Sunset Graze, Bold Rider and Ambush.

The western pulps also pioneered the continuing (or series) character, and nowhere was this more apparent than in Texas Rangers, every issue of which chronicled the adventures of Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield.

Hatfield's gun-swift escapades were penned by Jackson Cole,

which was actually a house-name behind which labored a whole team of writers. Alexander Leslie Scott is the writer most associated with the pseudonym. He started writing westerns whilst still in his early twenties, and tried whenever possible to base his plots upon his own first-hand experiences. A prolific penman, he also went on to compose about 125 stories in the Walt Slade series, using the name Bradford Scott. Interestingly, the Walt Slade yarns are seen by some as the precursor

to such graphically violent westerns as the Edge series by George G. Gilman, about whom we shall hear more in due course.

The pulps went into decline in the 1950s, although the western itself continued

to enjoy immense popularity. But now it moved at an even greater clip away from its melodramatic beginnings and started showing a greater maturity. Western characters and situations were no longer clear-cut. Now, when the hero stopped a bullet, it hurt like hell and bled like a bitch. He made mistakes just like everyone else, although things invariably came out all right in the end.

Among the authors who best handled this new slant on the Old West was Lewis B. Patten, a former auditor and rancher whose complex characters rarely found themselves involved in situations that were any simpler. The Trial of Judas Wiley , Red Runs the River , The Orphans of Coyote Creek and Death Rides A Black Horse are all superior examples of this newer, more realistic interpretation of frontier life. Wayne D Overholser, a school principal, teacher and then full-time writer from Oregon, was equally adept at the form, as indeed was the always-impressive and eminently collectible

Harry Whittington.

The British western was still as formulaic as its earliest American counterparts, however, with hackneyed plots, sham dialogue and cliched characters. But the market for westerns here in Britain was huge -- and publishers weren't slow to exploit it. Brown Watson started issuing western anthologies as early as 1948, and Scion Books eventually published more than 80 western paperbacks, including "oaters" by such cult favorites as Webb Anders, Jim Bowie (a pseudonym for the prolific Victor Norwood), John Russell Fearn and V Joseph Hanson. Incredibly, Hanson's westerns would continue to appear under both his own name and the pseudonym Jay Hill Potter for

the next fifty years.

Transworld Publishers began issuing books under its famous "Corgi" imprint in 1951, and among its first three titles was Jack Schaefer's classic Shane. For many years thereafter, Corgi could lay claim to one of the strongest western lists around, with a "corral" of writers like Ernest Haycox, E E Halleran,

Max Brand, William Hopson, Paul I Wellman,

Luke Short, Frank Gruber and L P Holmes.

Indeed, it was Corgi who really launched Louis L'Amour. L'Amour remains the most successful western writer of all time, with worldwide sales well in excess of 175 million copies. What is even more remarkable, however, is that his books weren't simply based on research. L'Amour's main source of inspiration was his own extraordinary life, during the course of which he sailed a dhow on the Red Sea, was shipwrecked in the West Indies, handled

elephants at a circus and fought as a light-heavyweight boxer, winning 51 of his 59 fights!

In 1958, Brown Watson launched its Long Loop

imprint, and went on to reprint many hardcover westerns by the likes of the prolific Irish writer Albert King, but there is no doubt that their most famous "son" was J T Edson.

Nottinghamshire-born J T Edson first started writing whilst

still at school, and entered a Brown Watson literary competition in 1960. When his novel Trail Boss took second prize, he was quick to follow up on his initial success and submitted two more manuscripts, The Hard Riders and The Texan. Right from

the start, Edson's westerns chronicled the exploits of "The Floating Outfit", a sort of mobile fighting force under the control of wheelchair-bound Ole Devil Hardin.

Corgi maintained a strong line of westerns throughout the 1960s,

reprinting many of the Hopalong Cassidy novels of Clarence E. Mulford and the Sudden westerns of Oliver Strange. Their only really serious rival in the western stakes was Hamilton & Co, later Panther Books, who issued some beautiful-looking

westerns throughout the 1950s and 60s. One of their best writers was Matt Chisholm (real name Peter C Watts), whose westerns were always distinguished by tremendous style and authenticity. If J T Edson was the most successful British western writer, then Matt Chisholm was certainly the most accomplished.

Australian publisher Cleveland was also quick to spot and exploit the popularity of the western, a genre which they continue to publish even today. Their most famous writer was Leonard F. Meares, best-known under his Marshall Grover pseudonym. For more details about Len's life and work, check out the separate page we have devoted to him.

Meares wrote more than 700 books all told, but he wasn't the only writer working flat-out for Cleveland. Keith Hetherington was another prolific contributor, as both Kirk Hamilton and Brett Waring -- and as you will see when you check out our Keith Hetherington page, his high-quality westerns are still being published today, under the Black

Horse Western banner of Robert Hale Limited, where he writes as Jake Douglas, Tyler Hatch, Clayton Nash and Hank J Kirby.

The most prolific of the many prolific writers working for Cleveland, however,

just had to be Paul Wheelahan. Under four pen names - Emerson Dodge, Brett McKinley, Ben Jefferson and E. Jefferson Clay -- he wrote close to 900 westerns, and later published some great

western fiction under his own name, here in the U.K.

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, however, a tougher, harsher, and altogether more violent portrait of life on the untamed frontier began to emerge. Finn Arnesen, a western expert and editor with the Norwegian publisher Bladkompaniet A/S, best sums up what the reader of the day had come to expect; "They want a modern, realistic story with a factual background, also with a bit of sex and a touch of brutality. They want a hero who may throw up after he has killed a

man, who is changed and brutalised by his own acts of violence. They want women of flesh and

blood, with sexual cravings. They want realism."

Arnesen was describing Morgan Kane and his shadowy, violent world. Kane was the creation of former bank employee Kjell Hallbing, writing as Louis Masterson. The series, about a hard-drinking, hard-living, guilt-ridden Texas Ranger (and later U S Marshal) was a phenomenal

success in Hallbing's native Norway, where he galloped through more than 80 way-above-average

adventures, beginning with Without Mercy in 1971. Kane proved to be such a compelling character

that he also made regular, shorter appearances in Arnesen's fortnightly Western magazine. At

his height, there were even Morgan Kane playing cards!

Corgi picked up the series in the early 1970s and eventually published 41 English translations. In Britain, Kane's adventures ended on a high note with the classic Killer

Kane, but he never really caught on as a character here in Britain, although Kjell Hallbing

remained one of Norway's best-selling authors, and continued to chronicle Kane's adventures

for several years thereafter.

To a certain extent, Morgan Kane's thunder was stolen by New English Library's Edge series, penned by the accomplished British writer Terry Harknett and published under the

pseudonym George G Gilman. These ultra-violent westerns featured a cold-blooded half-breed

whose wisecracks usually formed the punchline at the end of each chapter. Two companion series,

Adam Steele and The Undertaker, testified not only to Gilman/Harknett's dominance of the market,

but also to the popularity of this new breed of western adventure.

Publishers - being publishers - were quick to identify this new market, and almost overnight the likes of Frank O'Rourke, Clifton Adams and Jack Schaeffer were replaced by a string of Edge clones, some of them better but none more successful than the original, and all of them written by a group of British writers known as "Piccadilly Cowboys" (the tag being that the furthest

west they'd ever been was to Piccadilly - in London's West End). These writers were Laurence

James, Angus Wells and John Harvey.

In almost every case, and as with Edge himself, the principal character was pushed into his violent life by a burning desire for revenge. Jubal Cade, in the novels by Charles R Pike

(a pseudonym initially used by Harknett, then Angus Wells, with a one-off assist by Ken Bulmer)

was, as the front cover copy told us, "a man trained to heal, but born to kill." He spent most

of the subsequent titles searching for the man who killed his wife. The life of James A Muir?s

Breed (in reality Angus Wells again) was turned upside down when his parents were murdered.

Cuchillo Oro, the Apache of William M James (Harknett and Laurence James, later James and Harvey),

hunted the army officer who killed his wife and son and mutilated his right hand. Herne the Hunter,

in the books by John J McLaglen (James and Harvey) was a gunfighter who gave up the violent life

to marry and settle down, only to come out of retirement when a bunch of drunken railroad passengers

raped his wife, an act which drove her to commit suicide.

John Ryker, alias Gunslinger, turned out to be the gunsmith who unwittingly